Photo Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest region

During the month of June, the jack pine forests in northern Michigan fill with the sweet trills of birdsong. Rare Kirtland’s warblers, flickering their grays and yellows through the trees, have arrived earlier this spring from their winter grounds in the Bahamas, to the jack pines where they breed and nest.

Today more than 2,300 breeding pairs use the lower branches of young jack pine each summer here—and in a few small forests in Wisconsin and Ontario. But just a few decades ago, the chance of hearing the male warbler’s distinctive song was approaching zero. One of the first species to be listed as endangered in 1973, after the Endangered Species Act was passed, this songbird’s population dwindled to only 167 breeding pairs in 1987.

The species’ turnaround came after years of dedicated conservation work to restore jack pine forests. Since 1992, American Forests has been working with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and other state and federal agencies to create habitat for the Kirtland’s warbler, which only breeds in the scraggly and quirky-looking jack pine. Concerted conservation efforts allowed the species to recover enough to be removed from the endangered species list in 2019.

Mitzy Sosa, American Forests’ senior manager of reforestation partnerships, says that the organization’s long-term commitment to Michigan’s jack pine forests means “we have played a huge part in the Kirtland’s warbler becoming de-listed.” Through an agreement with the State of Michigan, American Forests continues to provide funding to the DNR to support planting one million trees per year and maintain this habitat for the Kirtland’s warbler.

This continued support is needed, as these forests will need ongoing care for the Kirtland’s warbler to thrive, says Jason Hartman, a silviculturist for the DNR’s Forest Resources Division. “It’s a species you can’t walk away from,” Hartman says. “You constantly have to be managing these forests.” And it takes a wide variety of partners including the United States Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service, to name a few.

Creating “Fire” Through Forestry

Part of the problem for Kirtland’s warbler’s has been their very specific needs when it comes to trees. Once a jack pine gets past its 15th birthday, it begins dropping the lower branches that the warblers seek out for protection as they build their nests. In the past, natural fire cycles support warblers by clearing and regenerating patches in the forest—creating places where warblers could nest and forage for insects and berries. The fire’s high heat opened the jack pine’s seed-rich cones, kickstarting the growth of the next generation of trees, says Hartman.

But with people now building homes and lives at the forests’ edge, Hartman says, “you can’t let fires do their thing.” Since wildfires started to be controlled in Michigan, where close to 90 percent of the Kirtland’s warbler population spends its summers, the warblers began to decline with the rise of wildfire suppression.

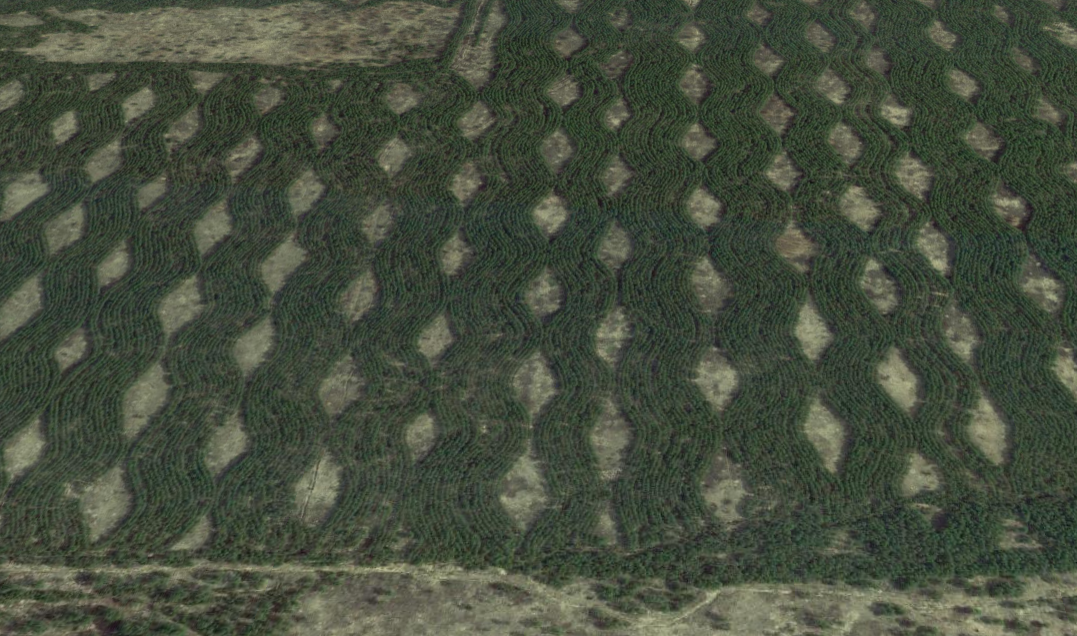

To mimic the clearing that fire has historically provided, Hartman and his team use timber sales to fund restoration work that creates large open areas. Trees are planted in a pattern called the opposing wave that, from above, looks like undulating waves. The new jack pines that will grow into the young trees that the warblers seek out when they arrive after their more than 1,700-mile migration.

The scenario is not typical, Hartman says. “When you think about endangered species, you’re usually thinking about protecting old growth forest.” But for the Kirtland’s warbler, converting old forests into young forests helps these birds find the habitat and food they need to support young nestlings.

Along with maintaining a jack pine planting and cutting cycle to create warbler habitat, the State of Michigan is also planting red pine and other species, to provide natural variation of vegetation within the landscape, Sosa says.

This work supports not only the warblers and a more-diverse forest landscape, but local communities as well. The jack pine trees harvested as part of shaping warbler-friendly habitat are used commercially for both pulpwood and lumber. “It’s a benefit—one, for the environment, and two, for the people that depend on that work and the timber and wood products that are being produced by those forests,” Sosa says.

Threats from Cowbirds Wane

Another problem that has accompanied the loss of breeding habitat for the warblers has been the brown-headed cowbird. These birds are native to the area but often considered a nuisance species because they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests. The Kirtland warbler builds its nest on the ground, sheltered beneath the jack pine branches—and when a cowbird lays its eggs here, the young cowbirds hatch first and grow quickly, taking food intended for warbler nestlings.

In 1971, wildlife managers began trapping cowbirds to prevent them from taking over warblers’ nests, removing close to 4,000 of these birds annually. But as the warbler population rebounded, the cowbird population declines allowed researchers to consider reducing the number of traps. It’s a tactic that appears to be working—in a 2019 study in the Journal of Wildlife Management, a team of scientists found that even when trapping ended, fewer than 1% of warbler nests had cowbird stowaways.

While sustaining these forest communities will continue to require the efforts of forest managers like Hartman and his team, the thriving warblers are evidence that this work makes a difference. The population is back,” Sosa says. “And if you travel up to Michigan during breeding season, you can find them pretty easily.” All you have to do is listen for their beautiful song.